PNB Looks to the Future of the Form in Beyond Ballet!

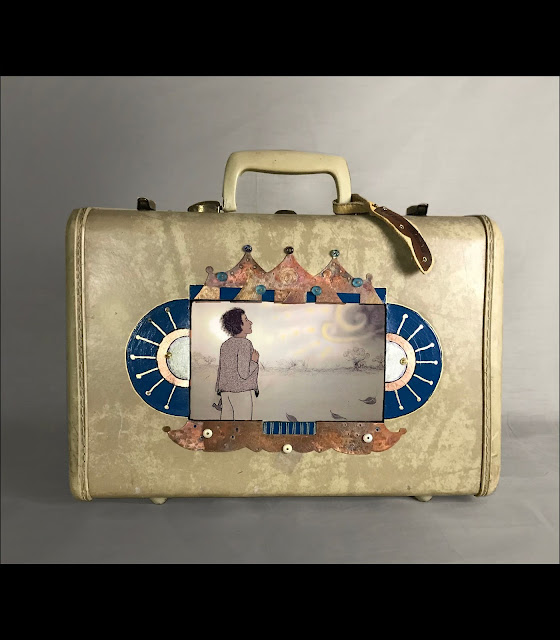

Pacific Northwest Ballet soloist James Kirby Rogers and corps de ballet dancer Christopher D’Ariano in Ulysses Dove’s Dancing on the Front Porch of Heaven, which PNB is presenting on a triple-bill with works by Alonzo King and Jessica Lang, onstage at Seattle Center’s McCaw Hall November 5 – 7, and streaming digitally November 18 – 22. For tickets contact the PNB Box Office, 206.441.2424 or PNB.org. Photo © Angela Sterling.

To be

completely honest, something happened to me at Pacific Northwest Ballet’s Beyond

Ballet that very rarely occurs. Yes, ladies, gentlemen, boys, girls (and all

of you with much more interesting and infinitely more deconstructive gendered

positions,) your hard-boiled, absolutely aloof and distant art critic/ballet reviewer,

just might have been moved to the point of tears during one of the night’s dances. But, in order to also set the record straight—I’m not

really all that hard-boiled or at all aloof, actually—but y’all already knew

that, I’m sure! We’ll talk more about what

moved me in a bit, but first let’s talk a bit about how the past affects the

future, and, as Miss Shirley Bassey once crooned, it’s all “just a little bit

of history repeating itself,” over and over, and over and over—honestly!

Since

the very beginning of my tenure as an art critic, beginning at the University

of Nevada Reno and UCDavis, postmodernism has been on life support, breathing

its last breaths. While some people

still cling to the idea that we are living in Post Modernity-proper, it has

become increasingly clear that this era, right now, (the one that is occurring will

you sit in front of your computer, which by the way needs a good cleaning,) that

this here age, has its very own obsessions, limitations, and goals; but that a

concrete philosophy has not quite solidified around it—at least not to the

point that anyone really feels confident enough to call the final curtain on it.

While I,

personally feel that Post-Modernism actually ended with the fall of the Twin

Towers and the death of the concept of the all-powerful hegemony, upon which

late postmodernity built its theses, it apparently continues to take more time

before the academy actually has the testicular fortitude to name this new era we find

ourselves trapped within.

But that

has not stopped things from pushing and evolving—attempting to become zeitgeist—attempting

to capture and encompass the spirit of this age. Until it finally does, however, we will have

to continue to live in a new time of “Mannerism,” just as everyone did after

the Renaissance gave way. PNB’s title “Beyond Ballet” actually kind of alludes to

this shift in perception and signals not that any of the dances included in the

night’s program show a direction beyond “Ballet,” (though, at least one of them

actually does,) rather it signals the desire, the overriding need for there to

be a possible direction—a proof of a possible future—a proof of a way out of the

recurring themes of an age that has long since passed its sell-by date.

For the sake of any easy-to-work-with definition, let us consider

"Mannerism" to be a period that is a break of sorts from the

traditional styles of a time, a break from the classical, but also a

continuation of it and a growth from it, generating work that tends to be more

stylistic and individual than it is about replicating the accepted rules of

what is considered classic, rote, etc.. It is then, a kind of collecting,

internalizing and understanding of the rules, elements and tropes of a previous

period and taking that knowledge to play with these tropes. In essence, a

Mannerist period is one in which artists take and make the tropes, styles,

tricks, aesthetics, philosophies, limitations etc. of a time and bend them to their will,

making them their own. Essentially, it is play after the rules have been set,

internalized, and understood.

It is an

era, which, while not necessarily pushing a form beyond its limitations and programs

rather falls back on personalized narratives and stylistic decisions, techniques

and novel ideas—because during a Mannerist period, the overriding artistic desire is not to remake the rules but to bend them to one’s own image. In a way, this

mannerism signals the final stages of an era—or at its best it begins to jumpstart the beginning of a new one.

Allow me

to tell you a story. Back when I was a child, the first art exhibition I ever

saw was an installation at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It was an

exhibition of Mannerism in which all of the paintings and sculptures were of women and men

with the most translucent white skin and the longest of all possible long

necks. It was a group show, involving several mannerist artists and included

paintings and sculptures of the first mannerist period. The artists had reworked

anatomy to the point that it no longer had anything to do with reality—think of

Ingres and his reclining nude with the extra bones in her back and take that

many steps further.

When I

first saw these paintings and sculptures, I became frantically worried, but also

intrigued and thought that perhaps this meant that there was another race of

creatures on our planet, all of them with ridiculously long necks and perfect

skin. I took these paintings at face value, and I asked my mother if they were,

in fact, aliens. She just smiled and said that was the style of the time, that

the artists painted not what they saw, but instead they painted what they

wanted to see—they were creating worlds as they wanted them to be. This

conversation is one that has always stayed with me and which I believe applies

here!

Beyond

Ballet is made up of three very interesting and very timely dances—each one chosen,

seemingly, for how they exemplify our current circumstances and especially how these choreographers

and artists have had to adapt when the forces outside of the ballet, those beyond the ballet exert more power than the forces from within. From Aids to how we have had to

adopt social distancing in order to simply survive this treacherous era. It’s an enjoyably

strong and steady presentation that has everybody at their best.

Pacific Northwest Ballet principal dancer Kyle Davis in Jessica Lang’s Ghost Variations, which PNB is presenting on a triple-bill with works by Alonzo King and Ulysses Dove, onstage at Seattle Center’s McCaw Hall November 5 – 7, and streaming digitally November 18 – 22. For tickets contact the PNB Box Office, 206.441.2424 or PNB.org. Photo © Angela Sterling.

As part

of PNB’s repertoire for 15 years, the night begins with Ulysses Dove’s 1993, Dancing

on the Front Porch of Heaven, which deals with the Aids Crisis and the toll

it has taken on all of us. Dove is known for his “relentless speed, violent

force, and daring eroticism,”—all of which are in play in this choreography,

which could have just as easily been entitled “Ghost Variations” and made

exactly the same sense—I suppose that may mean that these two dances were chosen together wisely.

The

actual Ghost Variations by Jessica Lang is a product of the current pandemic,

but like “Front Porch,” it spends far too much of its energy nostalgically channeling the

past. It is almost as though Lang was

too concerned that the audience would find the shadow dancers to be too strange

so everything else fell into the realm of the “safe,” and at times, even, the “cliché.”

Her choreography would have just as

easily been done 50 years ago as twenty or thirty, but that should not be taken

to mean that it was timeless.

As a

response to the limitations of the pandemic and to the needs of “social

distancing” using a large scrim upon which shadows are “thrown” is a pretty darned

good solution. But in practice, the

concept of dancing with one’s own shadow is so clichéd, so comical that even

Burt Bacharach has a song with the same name!

At moments “Ghosts” gets a bit too silly, too narrative, too obvious--reminding one of “Mary Poppins”

or some other Disney blending of reality and cartoon. I mean, it was fun and at

times I found myself laughing out loud and not always for the best reasons, but

the piece was at least enjoyable. It is

here that I want to add that the ballerinas and ballerinos on the other hand, were absolutely perfect and

hold no blame for any of my criticism. These dancers were thoroughly wonderful

throughout and that can and should be said about the entire night—everyone on

the stage was completely and impeccably en-point and you could tell that they

were thoroughly excited to be back on stage—and as a reviewer I need to confide

that it was really nice to be back watching them strut their stuff.

Pacific Northwest Ballet company dancers in Alonzo King’s The Personal Element, which PNB is presenting on a triple-bill with works by Jessica Lang and Ulysses Dove, onstage at Seattle Center’s McCaw Hall November 5 – 7, and streaming digitally November 18 – 22. For tickets contact the PNB Box Office, 206.441.2424 or PNB.org. Photo © Angela Sterling.

Enough of this gushing, or maybe not, PNB’s premiere of Alonzo King’s The Personal Element was simply on another level to the other pieces. Like I said before, watching “Element” I was definitely moved. The tears snuck up on me, for a moment I wasn’t even sure why I was crying and I stuffed those tears back up inside and then all of a sudden it was too late, my face was wet! When I say that it snuck up on me—at first—I didn’t understand why I was having such a strong reaction, but then I began to realize that while the earlier two choreographers had been searching for their inspiration in the past—King’s movements owed their existence to the movements to Now—to the nowness of the everyday—King’s dancers were not just dancing—this was a psychodrama. His dancers were not just politely dancing together or trying to tell us a romantic story—at times you could see quite clearly they couldn’t even stand each other—at times there was very definitely a fight going on on that stage. It was thrilling!

This was not a Pas de deux—at all! At least it was not one in the traditional sense, or in the same way that the others were playing this night, instead, this was about life. It came from life and it was about control and dominance/domination—but it was not about submission. More importantly King’s choreography was about escape and achieving freedom and it is all about the body—our very real, physical, straining bodies. When King’s bodies stand on tippy-toe—you feel the weight of these bodies crunching down on a point of singularity—his bodies, like the moves they project live in the same world as we do. But unlike many other contemporary choreographers whose reality comes from the sporting world, King’s is more jejune, more sporadic and chaotic—not celebrating the team/corps aesthetic that Ballet already leans towards, and which is an easy route to take. King begins to deconstruct our expectations and does not seem to fall back on the modernist clichés of Avant-Gardism—he appears to be intent on finding other, less well-traveled pathways out of ballet! And, if any of these choreographers on Beyond Ballet’s stage have a swinging chance—if Mannerism is in fact about reaching beyond oneself in an attempt to grasp onto the future—perhaps, King’s moves might even give us at least one avenue into whatever it is that is after this Postmodernism thing that we have trapped ourselves inside.

Comments

Post a Comment